George Wyatt wrote the first ever biography of Anne Boleyn, entitled The Life of the Virtuous Christian and Renowned Queen Anne Boleigne, in the early seventeenth century. George was the grandson of poet Thomas Wyatt, who is believed to have had a romantic relationship with Anne before she caught Henry VIII’s eye. George Wyatt claimed that his informants were two women, one of whom served as Anne’s lady-in-waiting:

“And, indeed, chiefly the relation of those things that I shall set down is come from two. One a lady, that first attended on her both before and after she was queen, with whose house and mine there was then kindred and strict alliance. The other also a lady of noble birth, living in those times, and well acquainted with the persons that most this concerneth, from whom I am myself descended.”[1]

Samuel Weller Singer, the nineteenth-century editor of Wyatt’s work, identified the lady from Anne’s household as Anne Gainsford.[2] Historians accepted Weller Singer’s erroneous identification of a maid called “Nan” as Anne Gainsford even though, in the words of Anne Boleyn’s most prominent biographer, Eric Ives, “given such links, the volume of material Wyatt recorded is disappointing”.[3]

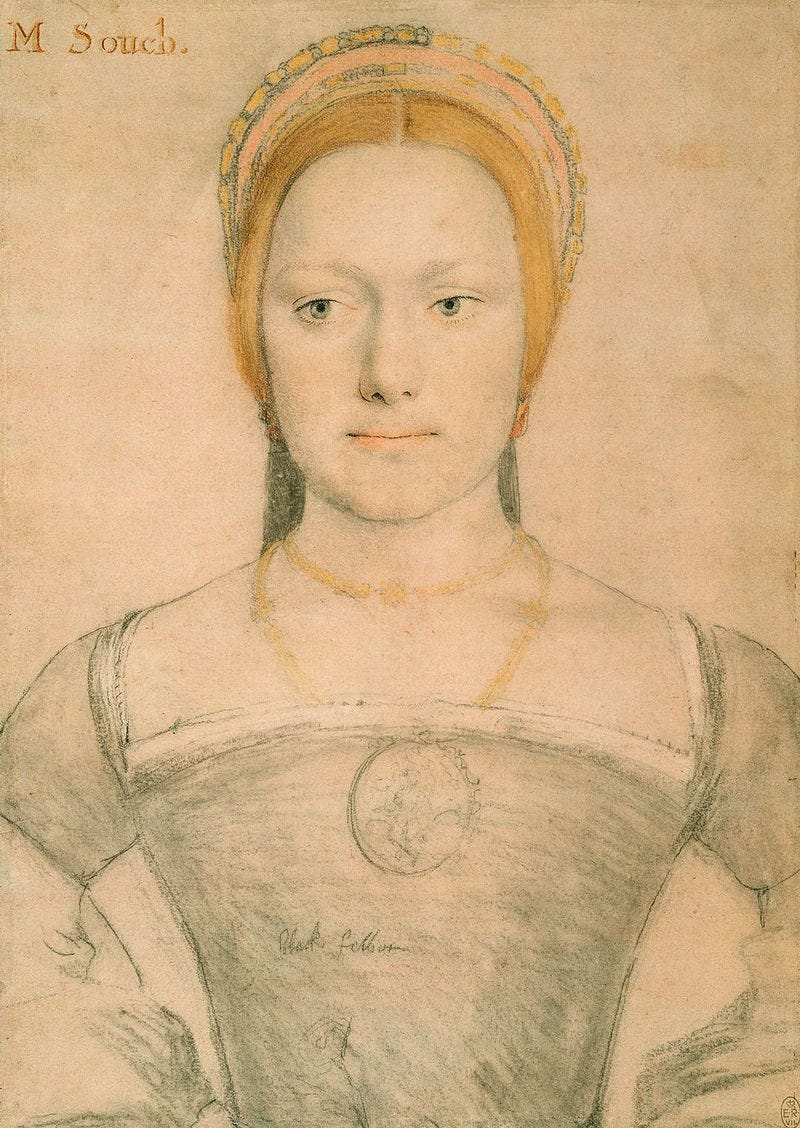

Weller Singer was wrong in his identification because Anne Gainsford died before George Wyatt was even born. In his last will dating to 16 July 1548, George Zouche, Gainsford’s husband, made it clear that he had remarried since he mentioned “Elleyn now my well-beloved wife”.[4] Sir George Wyatt was born c. 1553, some five years after George Zouche’s last will was written. Weller Singer’s identification of the maid serving Anne Boleyn was influenced by Wyatt’s description of an incident with a woman of Anne’s household reading a banned book that ended up on Cardinal Wolsey’s desk.

This woman was identified as Anne Gainsford by John Louth, Archdeacon of Nottingham, whose reminiscences were published in John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. By the time Weller Singer edited and published Wyatt’s work, Louth’s account of Anne Gainsford, George Zouch and Anne Boleyn, all reading William Tyndale’s The Obedience of a Christian Man, was already well-known.[5]

Weller Singer included Louth’s reminiscences in his edition of Wyatt’s biography. The two book incidents were very similar, but the chronology in Wyatt’s account is muddled; he describes that it happened following Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn’s wedding in January 1533 and has Wolsey interrogating the maid’s suitor, though Wolsey died three years earlier.

Anne Gainsford died before George Wyatt was even born; this little detail escaped historians who repeated that she was his informant.

Footnotes:

1 George Wyatt, Extracts From the Life of the Virtuous Christian and Renowned Queen Anne Boleigne, p. 181.

2 Ibid., p. 180.

3 Eric Ives, The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn, p. 52.

4 David Graham Edwards, Derbyshire Wills Proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, 1393-1574, p. 106.

5 John Louth, The Reminiscences of John Louth, Archdeacon of Nottingham, Written in the Year 1579, in Narratives of the Days of the Reformation, p. 52.

—

If you like my posts, you’ll love my books! This article was based on Ladies-in-Waiting: Women Who Served Anne Boleyn.

Given that George Wyatt was writing quite some time after Anne Boleyn was executed, shouldn't he also be taken with a huge sugar lump the same way that Father Nicholas Sander is? The latter is dismissed because his account is anti Anne, anti Elizabeth and anti anything to do with them because he wrote to criticise the persecution of Catholics in England and to discredit the Queen of England. However, George Wyatt also has an agenda, to write Anne up in glowing terms. It's pretty obvious that his account is also full of patched over holes. So why dismiss one and not the other? Surely both works should come with the same warning of caution?